- Home

- Sylvia Taylor

The Fisher Queen Page 4

The Fisher Queen Read online

Page 4

“Holy shit, Paul, it’s Mother’s Day! I can’t believe we’ve only been gone five days. It feels like five months. Look, it’s May 18th. I’ve got to get hold of Mum and Dad to let them know I’m okay. She will be freaking. Is there a phone at the camp I could use and reverse charges?”

“We’ll have to see when we get there. The camp is barged in every year by tugs and things can change. Depends on who’s managing and if they have a decent connection after that storm. Maybe you can ask the manager if you can use his phone real quick. He might be sympathetic to a cute girl who wants to call her mum on Mother’s Day,” he said with a grin.

We did have some capacity for long-distance calls on our radio telephone, but it was incredibly expensive, especially to Clinton, in the Cariboo region of BC’s interior where my parents had retired. It was only for extreme emergencies because the call would have to go through the Coast Guard and be patched into BC Tel. I had told my mum that if they ever received a patched call it would be very serious, which had reduced her to heartbreaking tears. There were other phones that could be patched straight into the telephone system, but they were a fortune and, needless to say, we couldn’t afford one—or the calls.

My mother, who had suffered through countless sleepless nights over my adventures, had been completely beside herself when I told her and Dad that I was going commercial fishing with Paul up north. Whitewater canoeing for a weekend was one thing, but a boat in the middle of nowhere, where every imaginable (and she had a great imagination) thing could maim or kill you in an instant? That was more than she could bear. She had already seen and experienced unimaginable suffering and destruction growing up in northern Italy during the Second World War and knew all too well what could happen to a human being. And I was her baby, the first-born, her only link to my father when they were separated for long periods and distances in their early years together. She had already endured the loneliness and isolation as a beautiful young woman coming to Canada and living alone with a child in Edmonton, then fledgling Vancouver, while my father toiled in constant danger in remote lumber camps in northern Alberta, then northern Vancouver Island, before forming a successful construction company.

As a tow-headed farm boy, my father had been flung into the horrors of fighting for his beloved Latvia and then into camps as a Displaced Person. He later followed his heart as a gifted musician and arranger in northern England, where he met and married my mother and I was born. And now they were two middle-aged mismatched folks living quietly in the middle of 160 acres of high pine forest in the middle of the Big Bar ranching district where my father had finally found home.

He was not frightened or worried about me, believing in his deep Nordic heart that Mother Nature would always keep me safe and bring me home to him again. He hung on every word of my colourful stories, sky-blue eyes shining with chip-off-the-old-block pride. Before the fishing season, the last thing he’d said when he crushed me in his hug was “Remember to call your mother—this is going to be tough for her. Write me a letter now and again. You write as good as you talk.”

If I’d known how early he would be taken from us, I’m not sure I would have let that hug go. But what he held closest to his heart was knowing that I carried his spirit of survival and a hunger for life.

“Hey, how about rustling up some grub, there, deckie,” Paul said, smiling, and jerked his thumb over his shoulder to the galley. “That porridge ain’t gonna cook itself and we have another couple of hours before we get to Bull Harbour.”

“Aye-aye, Captain Honey.” I saluted smartly.

“I’ll have ye keelhauled for insubordination.”

“You’ll have to catch me first,” I said, relieved that his brooding had lifted. He and Mother Nature had a lot in common.

Keeping the cranky old oil stove on an even keel was an art and a science in itself, similar to turning lead into gold. It was either blasting hot or barely warm and went out completely when it got rough. My experience drawing machine-engineering spec sheets for a living was definitely coming in handy now, if for nothing else than to save me from being completely mystified.

While he ate at the wheel, I took my bowl out to the deck and sat on the hatch cover in my jeans, gumboots and three sweaters, and watched my Brave New World open up and slide by. Land gave way to sea and horizon, at times completely—a very odd thing for a girl brought up in a city of mountains and rivers and the high sierras of the BC Interior. I was no stranger to the waters by canoe and sailboat, but the next five months were as unknowable as the ocean horizon that revealed the curvature of the earth.

Entering Bull Harbour off Goletas Channel was like one of those old King Kong movies where people stumbled upon a secret world tucked away from time and the familiar. Just when I thought we’d be flung out into the wild open seas beyond the channel, we slipped into a subtle little opening that wound a bit left, then right, and suddenly stunned us with a spacious bay carved into the port side of Hope Island—the last stop on the way to the Queen Charlotte Islands, two treacherous days north.

Glassy water reflected the low-slung land furred with trees dwarfed by powerful winds. Today it was a bustling place of fishboats loading and unloading, coming and going, from the two enormous barges that held an entire fish camp of ice houses, storage, general store, office, fuel tanks, water systems and floats. The portable factory town was owned and operated by BC Packers, the biggest and oldest commercial fish handler since the late 1800s.

I was like a terrier, scurrying around the deck to see everything all at once. Since the space along the floats was limited, we could tie up at the servicing dock only to unload fish or take on ice, fuel and water. Lots of boats had to anchor out in the bay, away from the clamour and the company. While the more reclusive folks preferred this, most fishermen tended to be friendly and sought out human contact and conversation like a Bedouin would an oasis.

Bull Harbour was the only fish camp north of Hardy, the entire top end, and for a hundred miles down the west side of Vancouver Island. The only place for fuel or water or the precious crushed ice that kept your dressed fish from turning to rotten mush over 10 or 12 days before offloading and uploading for the next stint—a blur of action called The Turnaround. Every day lost to weather or breakdown or hangover was a financial loss, never mind the exhaustion or injury.

After we registered our logbook, names and social insurance numbers at the office and made nice with the new managers, we spent the last of our money on diesel, cigs and a coveted chocolate bar, then filled up the sectioned bins with crushed ice and topped up the teeny water tank. After lunch Paul started the Talk Circuit. He strolled the floats, checked in with old friends, caught up on rumours and gossip, greeted strangers and occasionally remembered to introduce me. In time I would get accustomed to and even learn to ignore the bold stares, usually from older fishermen, the leering inquiries about whether I was looking for a job and the predictable curiosity about Paul and my personal status. But it was still early in the season and the men not long from their homes, so all was tolerable. Many of Paul’s pals were genuinely warm and friendly, welcoming me to the industry and acting almost courtly. Some of them would become very dear to me, and welcome havens in the tough days to come.

I hadn’t had so much coffee and nicotine since college, and between the chemical buzz and the excitement of starting fishing the next day, I was getting pretty jingly. Paul suggested we row to the back of the bay and hike across the narrow neck of woods to Roller Bay. Dave, the camp manager, hadn’t been too keen to let me use their phone to call my parents, but Marji, his sweetheart of a wife, melted like Mother’s Day chocolate and said I could make a quick call after dinner that night when things had slowed down at the camp. With a quick hug to her, we were off in our skiff to explore.

We made for the crossed trees that marked the trailhead. Bathed in warm sun and Paul’s assurances we’d only be gone a couple of hours, we brought nothing to eat or drink and wore only sweatshirts, jeans and sneake

rs. Full of fun and frolics, we set off at a jaunty pace until we came to a fork in the trail just inside the dense pine forest that rose like a fortress behind the scrub and salal of the waterfront. It was a toss-up which way to go. Since Paul couldn’t remember which side to take and both paths were equally untrodden and vague, that’s what we did: tossed a coin. Seemed like pretty much everything else was up to the whims of fate, so why not this too? We took the right fork and hoped for the best. How far could it be? We could already hear a faint rumbling, which we took to be the surf.

Padding along the spongy trail we fell into a silent, dreamy rhythm, lulled by the pulse of life around us. Vegetation didn’t just grow in the rainforest, it vibrated and hummed in a million shades of green so intense we could almost taste the chlorophyll. And today was particularly symphonic since it wasn’t being lashed by wind and rain for a change.

If the forest was Gaia the Earth Goddess’s heart, then the ocean was her breath, the draw of her mighty bellows. Growing louder ’til it resonated in every cell like a tuning fork. Some pre-paleolithic part of us heard and knew we were going home and prepared to slide back to meet it.

We stepped through the dark velvet curtain and onto a dazzling stage where another kind of Passion play unfolded: the marriage of sea and sky. It swallowed our jokes and glibness and all our silly little human concerns. We were blown out fresh and flat and simple as white sheets in the wind.

The waves rumbled us quiet, as we lay side by side on this beach at the edge of nowhere. The waves whispered us to sleep after we made love and nestled deep into our warm, pebbly mattress like salmon and dreamed our fishy dreams.

We awoke suddenly to the bellowing waves as we stirred and blinked in our chilly hard beds. The sun was racing for the horizon, kicking up spumes of smoky dust and setting the clouds smouldering. If we didn’t hurry, it would get home before we did. A moonlit trail may be romantic in Vancouver’s Stanley Park, but it was deadly out here.

Scrambling up the gravelly slope, we ran back and forth looking for the trailhead, like terriers looking for a rabbit hole. After a few false starts we found something familiar enough to call a trail and convinced ourselves it was the right one. It was not. We knew it but wouldn’t admit it. Where it had been spongy, it was now boggy. Where it had been lush, it was now forbidding with dark looming trees, massive ferns and dense tangled underbrush. The cool dappled light now blurred and ran together.

The more we needed to hurry, the slower we had to go—like trying to run in a dream. Like running underwater. I thought of those experiments I’d read about where people could actually breathe oxygen-suffused water without drowning. Maybe this was one of nature’s experiments, an attempt at creating another element. Everything seemed so saturated that one more drop and this whole place would burst into water. Soon we couldn’t step over or around the dark water. The pools ate up every inch of ground and the humus became porridge.

Even if we had been able to pick our way around the water and bog, it was blanketed by an endless morass of fallen trees, helter-skelter like a giant game of pick-up sticks. Most of them had been here long enough to grow thick shaggy coats of slippery moss, playing host to the next generation of flora. I looked down at my flimsy tennis shoes and prayed they would magically grow golfing spikes. There was no way around, just through.

We tried to keep moving in some general direction while zigzagging from one slightly more stable surface to another with the concentration of tightrope walkers. Though the moss underfoot was an enemy, the stuff hanging on live trees was a friend, showing us where north was in this surrealistic world. Or so we hoped.

Lost in some Alice In Wonderland fantasy, it seemed that the trees and ferns and moss had not gotten bigger but we had become smaller—I was certain of it. We had become four-footed, big-eyed, furry little mammals scurrying from one fallen tree to the next, criss-crossing this forbidding primeval swamp to find their burrow trail. Ears pricked for the sound of crashing reptiles, we wordlessly pushed on, saving our energy and breath, with only an occasional grunt to indicate a safer or shakier footing.

I wondered if we were really just wandering aimlessly and for how long our exhausted legs could hold out. How ironic, I thought, after everything we’ve been through, to die in a rainforest swamp less than two miles from our skiff and the lights of the fish camp. If we didn’t succumb to exposure—May up here was like March in Vancouver—we could slip off any one of these fallen logs and break a leg or rip our guts open on a spike or be swallowed up by bog mud.

But that was just bogeyman talk. I didn’t know about Mr. Ace Explorer, but I was going to make it back okay; I always would. I could feel Paul glancing at me to gauge my fear or resentment. He found none. I felt no fear because I had yet to experience its profound power. This was another challenge to be met and conquered, and I would be my father’s daughter. I took an almost perverse pleasure in survival. The car accident and my agonizing recovery had become my new benchmark.

Paul didn’t apologize or make excuses or try to help or reassure me. I had wanted equality in a man’s world and I was getting it, though I wanted some small token of love or pride or gratitude: a tender embrace, a you did great, an I’m a lucky man or a thanks for being such a damned good sport.

According to my father, I was one of nature’s beloveds, and as such, the Nature Spirits would always protect me. And they did, then and countless times to come.

“What are you smiling about?” Paul said in the dimming light.

“Everything,” I said as a faint trail appeared in the soggy ground.

“Daddy, can you hear me? You have to remember to say over,” I shouted into the mouthpiece at the fish camp office and forgot to say the critical over so he would know when to speak.

“There is no problem with the line,” he rumbled in his lilting accent. “But your mother is crying so hard I can hardly hear you. Angela, for God’s sake, calm down. Everything good here, except for your mother worrying herself sick about you. Lots of action around here lately. Your sister had her baby five days ago, another little girl. Your mother is pushing for Lisa Gay. It’s good you called for Mother’s Day, Sylvi.”

I heard my mother’s sobs and her burbled “Let me talk, Laimon.” My calm resolve started to melt away. My eyes filled with tears at my father’s voice and my mother’s sobs and I swallowed over and over to keep my voice steady. My little sister was a mummy again and my throat ached with nostalgia. I was an auntie again and I had missed my niece coming into the world. I remembered the boundless joy of holding Jenny, Gay’s firstborn, in my arms just two years before, still bloody and slippery from the womb. Tears escaped. That world and that life already seemed surreal, like that was the movie and this was real life.

“Sweetheart, it’s Mum. I’ve been so worried about you; are you alright?” she sobbed. “Just before you called I was sitting in the living room and thinking of you and when I was pregnant with you in England. I just found out and was so happy and Daddy was so worried because he wanted to wait until we went to Canada to have a baby. But I wanted you so badly, mia cara, and there I was on Mother’s Day, knitting you a little pink sweater, piccola bella bambina, because I just knew you would be a beautiful little girl. Born in January, my birthday present. And there you are now, grown up and so far away and doing something so dangerous. Are you okay? Tell me the truth. When am I supposed to say over?” Mum dissolved again in sobs, and with that came my own tears.

I didn’t know radio telephones broadcasted to every single person dialled into that frequency, which in this case was every person in the fleet, plus anyone anywhere near the external speakers at the fish house. The manager and his wife had discreetly moved to the next room. It wasn’t until Paul came into the office and signalled that it was time to end the call and we were walking down the long outside wooden stairway to the dock that he told me the reason people were snickering all along the way to our boat. I wasn’t even remotely mortified, having grown up with an emotive mum

, but laughed so hard I teared-up and could hardly climb onto the boat. Paul, a tad embarrassed, said people would be chuckling about the incident for days. I said I thought it was often safer to laugh over something than to cry, especially in this world where we had to keep a tight rein on our emotions.

I would come to understand how that became a survival mechanism for most people living dangerous lives.

We went to bed early, thinking that would give us the good night’s sleep we would need for our first day of fishing. But sleep would elude us as we lay in our separate bunks, mine from excitement, his from worry.

First Day Fishing

My psychic requisition for our first day of fishing must have gotten mixed up with someone else’s, because instead of a beautiful calm day filled with spring salmon flying over the stern and into the checkers, we got someone’s request for a day in hell. There is an old Yiddish proverb that says: If you want to make God laugh, make a plan. God was having a real knee-slapper.

We tiptoed out of Bull Harbour at 5:30 a.m. with a few other brave souls who decided to tough out the reports of rising wind and seas coming down from the north. Hitting Goletas Channel after the sheltered calm of the bay was like being grabbed off the sidewalk and thrown onto a roller coaster. Massive rolling waves shoved their way down the narrow channel from the open seas beyond, angered by the sudden shallows of Nahwitti Bar at its mouth.

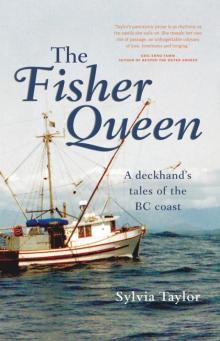

The Fisher Queen

The Fisher Queen