- Home

- Sylvia Taylor

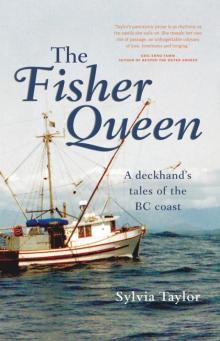

The Fisher Queen Page 5

The Fisher Queen Read online

Page 5

“Jesus, it’s gonna be a rough ride out to the grounds. Hang on. You okay?” Paul quickly glanced over to see me already positioned like a sumo wrestler in the wheelhouse, feet apart and knees flexed, arms spread, hands clutching the dashboard. I knew all about keeping my balance and protecting my joints: stay loose, flexed, stable, and keep breathing, deep and slow. “I’m okay.”

“It’ll get better once we’re over this fucking bar. We’ll go straight out a couple of miles to where the shelf drops off at 50 fathoms, that’s where feed gathers, and we’ll turn west and start trolling along the edge. It’s called the Yankee Spot and runs all along the top end of the Island. There’s another fishing grounds about 12 miles offshore. Hey, did you take the coffee pot off the stove and put it in the sink? Okay, good. Anyway, that one is called the Steamer Grounds. The weather gets pretty wild out there and it’s a long run in.”

“So what can I do today?” I was relieved that at least there wasn’t big wind along with the big waves, but the lowering gunmetal sky seemed to be preparing for some kind of assault.

“If the pilot holds out, you can come out to the stern and help lay out the gear in the cockpit, but I just want you to watch while I set out the gear and pull it in. You’ve got to know what you’re doing back there or you can get into a hell of a mess and the gear is a fortune. One box of a dozen flashers is 57 bucks, and we can use 60 or 70 at a time.”

“I’ve seen the bills. We’ve already spent almost $2,000 on gear. I’ll be careful, I promise.”

“When we get near the edge in a few minutes, I’m going to slow down to quarter-speed for trolling, about two or two and a half knots, depending on waves and current. You’re going to keep the bow straight into the waves so we can be as stable as possible while I drop the poles. In heavy seas like this it can be very tricky, so we have to do this quick. When the stabies are in the water it’ll be safe to turn the boat broadside to the waves. I’ll come back in and set the pilot and hope the bloody thing works, and you can come out the stern and help me set gear. Okay . . . here we go. You ready? Get up on the seat here and take the wheel.”

Heart pounding, I focused on riding straight into the looming swells. I can do this. I can do this. I would do my part to keep us safe while he did his.

It was very unusual to run with stabilizers unless it was deadly rough, as they slowed the boat down and ate up fuel with their heavy drag through the water. When trolling they were mandatory and settled down the boat considerably, not only with the 40-pound stabilizer boards in the water dragging on chains, but with the two 40-foot stabilizer poles, which were tied by ropes attached to cleats on the mast; they dropped the weight and centre of gravity down to about 45 degrees.

We had to let the stabilizers and their complex system of ropes and pulleys up and down by hand. They were so heavy I could let them out only by inching out the rope still wrapped once around the cleat, but I couldn’t bring them up from the flattened position. If the rope got away from us, especially in rough waters, and if the pole dropped to the end of its ropes, we could tear up rigging and bust the bolts fixing it to the deck. We had to let them out smoothly and quickly, one after the other with just one of us or simultaneously if there were two of us, because just having the one side down destabilized the boat—especially dangerous in rough seas. If one set of ropes broke or tangled, we had to balance out with the other pole in the same position.

Typically you ran from your anchorage if you were pulled in for the night in sheltered waters or if you were tied up at a wharf. Usually you would go from anchorage straight out to the grounds, running with poles up, then slow down to trolling speed while still heading out, especially if you were nearing a whole grid pattern of boats trolling over a hot spot. If you had a good pilot, you would set it going straight out then lower your poles right away. If it was really rough, you slowed it down to half-speed because moving forward faster kept you more stable. If it was really, really rough, you always set the pilot straight into the waves, and if it was super rough, someone would have to steer into the waves—like now.

Paul quickly stepped aside as I flipped up the steering seat, braced myself against it and gripped the heavy wooden wheel. Never taking my eyes from the dark water crashing over our bow, I heard him grunt a final okay and the cabin door slam. Felt the whir and vibration of the rope running through the pulleys and knew Paul had started. I had done this before but not in such heavy seas, and when the boat lurched to one side as the pole and stabie went down, my heart kicked up a notch, waiting for the whir of the second rope. Any twist or knotting in the ropes would hang it up, and I knew enough to know that we would be in serious trouble. I rolled my shoulders and breathed deeper.

The clunk and splash and righting of the boat created an odd sensation of a slow-motion roller coaster and I thanked my genes again for my absence of nausea. Paul was back in the wheelhouse, pretty revved up.

“Okay, all done, you did great. Now get your rain gear on and go out to the stern and wait for me in the cockpit. Don’t touch anything. It’s pretty rolly, so be careful, especially getting into it—it’s a long way down for you. I’m going to turn west onto the tack and set the pilot and keep an eye on it from the stern controls. There’s hardly anybody out here to run into and we’re pretty clear of pinnacles and reefs in this area. If the pilot fucks up you’ll have to come back and steer.”

It was rough and cold and miserable, but I was excited as hell getting into my shiny orange Helly Hansens. I already had on four layers of cotton and wool and leotards under my jeans and to that I added two pairs of grey wool work socks and black heavy-soled gumboots. The small-size bib overalls cinched tight and the hooded jacket had already been adjusted as much as possible to fit my 5-foot-3-inch self, with the bib ending up at my neck and the sleeves folded up twice. For now the trailing waste strap would wrap around me once. As I melted away over the months, it would wrap twice. The red toque I had crocheted for the trip completed the ensemble.

A cautious crab-walk got me to the stern in the heavy side-roll, where I carefully knelt on the lidded checkers (we would undoubtedly fill them with fish today) and slid down into the starboard side of the cockpit that I had decided would be my side. By then Paul had swung us into our westward tack and I watched the sullen, low shore slip by. Offshore there was an odd, dark density that seemed too low for clouds and too close for horizon.

I was grateful it had been so lovely the day before but sincerely hoped this bipolar spring weather would settle down soon. I had yet to learn that the North Coast never settled down and was as quixotic as the people were courageous.

“Okay, let’s hope the pilot holds out. Jesus, you’re in no danger of falling out.” Paul laughed and took the lid off the wooden gearbox running along the back of the checkers. “You’re up to your armpits in here. This is what you can do—get the gear ready for me. Remember how we stowed each rolled-up line of Perlon and lures and clipped it together with the snap? I want you to carefully unroll them by holding the snap and gently throwing the rest behind the boat to trail in the water, then snap it to the wire nailed across the cap rail. You have to make sure it’s clipped on tight or you’ll lose it and that’s 5 or 10 bucks down the tubes. Line a few up and I’ll start setting the gear.”

“If I watch you set your side, can I set mine?”

“No, not today. You’re always in such a rush to do things. Take it easy.”

I knew it was pointless to insist. We worked together in concentrated silence as he explained how BC boats could drag six steel lines through the water, three on each side, weighted down with a lead cannonball weighing between 25 and 70 pounds. Ours were 40 pounds and stored in cup-shaped metal holders bolted to the side cap rail, a long reach from the cockpit when setting gear. Each 1/16-inch steel line of up to 150 fathoms (six feet to the fathom) was held on a hydraulic drum called a gurdy, three to a side, which played out one line to a system of bells and triggers spaced along the pole. The lines were submerged and

set with gear one at a time, starting with the bowline, then the midline, then the pig line, so named because of the two-by-three-foot rectangular Styrofoam float attached at the line’s midpoint, which caused it to swing out and keep the lines apart in the water.

As Paul slowly played out each steel line from the gurdy, its cannonball descended to a depth calculated by the number of sets of two metal beads fixed to the wire at one to three fathoms along the line. Each piece of gear was clipped between the two beads by its snap and gently trailed in the water, one after the other. When fully set, a troller resembled a butterfly above the water, while below, set 5 to 10 fathoms above bottom, it trailed scores of twirling lures that mimicked herring and the colourful, squidlike hoochies that were the spring salmon’s dinner. The depth sounder in our cabin continuously flashed numbers that could mean bottom, fish, sunken wreck, reef, pinnacle or anything else its signal hit on the way down.

Bells on the stabilizer poles’ rigging could signal a smiley, slang for a spring salmon over 12 pounds. But sometimes the bells didn’t work and your fish got beat up by being dragged, or were eaten by seals, or if they weren’t in season, died before you could shake them off. A good fisherman kept the gear moving up and down all day to simulate a school of feed, or feed ball moving in all directions, instead of just swimming in a straight line.

You pulled in the gear one line at a time so the other tow line kept fishing and to avoid a gear-tangling catastrophe. Normally, an experienced fisherman could go through all the gear, both sides, in a half-hour or so, but this session was a two-hour slow-mo’ event as I absorbed every piece of action and instruction. The latest installment of Gear Setting 101 came rapid-fire but sequentially, and I vowed to myself that I would learn faster and more accurately than any other deckhand he’d had. I watched and nodded in profound, silent concentration. I relished the vertical learning curve, but I was restless for an action curve.

It was too rough and wet for me to write notes in my rapidly expanding Sylvia’s How-To Book right then, but I would as soon as I could. I took notes as much as possible while Paul instructed and demonstrated. Some of the instructions became large-print bulletins that soon papered the cabin walls: How To Start & Stop the Engine, How To Call A Coast Guard May Day, How To Light the Stove, How To Set the Pilot. He delivered his calm, pedantic sessions like daily doses, prioritizing the must-knows, good-to-knows and maybe-later-knows. I mostly curbed my natural inclination to see and understand how everything fit together and tried to interrupt him only to check my notes and bullet-point lists with him. If not then, later in carefully chosen quiet times. Mistakes were costly in time, money and temper tantrums.

The odd grey wall I had noticed in the distance two hours ago seemed closer whenever I looked up from my marine classroom, and with a sigh Paul confirmed that it was one of the north end’s infamous fogs. When the weather lowered, you had wind or you had fog. And this one was like something out of a Hollywood horror B-movie. I watched in shocked disbelief as it moved, eerily dense and soundless, across our deck to shroud us, then the water, then the land. We couldn’t even see the pigs riding only 20 feet off our stern. Not an experience for a claustrophobic. Even I began to feel uneasy when I no longer saw land. The only thing we could still see were the six-foot waves still pounding our starboard side. Instinctually I became hyper-alert and spoke in whispers.

It was just as well the pilot broke down: I would have had to hand steer in the fog anyway, my eyes glued to the glowing radar sweeps that showed a vague representation of the coastline and, hopefully, other boats we might run into.

I kept one eye on the radar and the slowly thinning fog and another on a guide book to BC salmon I’d picked up at the Bull Harbour library. In the office, I learned the multiple names and life cycles of the fish I longed to get up close and personal with. I had heard so many different names I had to figure out which was what. It turned out each one had a Native name, a Canadian name, an American name and any number of nicknames.

All five species started out by hatching in the early spring in freshwater gravel stream beds up to 1,000 miles from the sea. They took from one to five years to travel downstream and through the ocean and then return to the exact spot they were hatched to lay and fertilize the next generation of eggs. The strangest part was that most of the species’ males dramatically changed colour and even shape, growing fierce hooked jaws and humped scarlet backs to ward off competing males as they journeyed through the return of their cycle to spray their milt over the eggs in a nest the female had made by squirming in the gravel. After their struggle to reach their stream and emerge the alphas, the couple’s mating was passionless and heralded a quick death.

In the royal court of Salmonry, the chinook was revered by the coastal First Nations as the king of salmon, the names it is known by in the US, though it is spring and smiley by current BC fishermen. They were the biggest, the showiest and the first to arrive on the fishing grounds. The early-season princely sockeyes, or sox, vied for the crown and won it: these second largest of fish became a focus when the much smaller cohos and pinks began to decline in the ’70s. The average sockeye, which started running early in the season and could be taken with the springs, could bring in $10. A holdful of those beauties could make your whole season. Cohos, or small-sized bluebacks, were the dukes and couldn’t be taken until July 1. The hefty chums, or dogs, were the servants of the court. Running late in the season and taken by net, they were destined for the canned market and institutional use. When canners wanted to glamour them up, they labelled them Fancy Keeta.

The lowly pinks—also known as humps, humpbacks or distasteful slimeballs—were small and hard to dress and worth pennies a pound, not considered worth a troller’s time, and were left for the netters until they earned their new name in the early ’80s: Desperation Fish. With runs of all the other species at record lows from 1980 to 1983, trollers would scramble for the pinks to save their season. No one knew just how bad it would get. Record-low runs and 18 percent interest rates, competing users and tightening restrictions on seasons and areas were moving in to form a crucible of their own.

For another three hours we rolled and bounced until the engine began to overheat again and about noon we had to pull in the gear, turn around and run back to Bull Harbour. We’d caught one 20-pound red spring that brought us $55 at the fish camp for five hours of rolling our guts out in the fog. At least we didn’t come back skunked, but it was a grim ride back with Paul fuming about the Taylor Curse, which basically amounted to everything he touched turned to shit, according to him. There was nothing I could do to jolly him up, struggling with a bit of angst myself.

So what do you do when you’re stuck on a boat and you have to get away before you come undone? Some people are adept at leaving internally: their spirit is elsewhere. It is certainly more efficient than having to leave physically. There are very few experiences more powerful and unnerving than trying to engage with someone who is so Teflon-coated that nothing sticks to them. Mighty handy for long periods on a boat, especially in isolation. Personal boundaries are a luxury, and so people go inward to find space. It is also free, instantaneous and infinite. But for those of us who are deeply engaged in the world and Velcro-skinned, detachment is illusive. What do we do? The irony of boat life is, though you’re surrounded by limitless space, there’s nowhere to go.

Paul and I were dying from constriction in the midst of endless space. I knew he was upset by all the boat problems, no fish and looming boat mortgage payments, but I had to get away from The Dungeon banging and didn’t have anywhere to go but the 40-foot float.

I noticed the skiff was still tied to our midships cleat where Paul had used it to inspect the intake valves for obstructions, and I got the brilliant idea to get away by rowing around the bay. I poked my head through the floor opening and told him my plan. He grunted in reply. I strapped on a life jacket and told our dock neighbour that I’d be rowing around. I knew better than to go out in the wilderness alone

without taking precautions.

With every pull on the heavy wooden oars I felt lighter, like leaving the gravitational pull of some dark planet. I imagined myself as a water bug, skittering weightless across the surface, then a swan, gliding and elegant. It was so blessedly quiet and calm, the air so warm and gentle, and I couldn’t tear my eyes from the ripple of my wake. My bones and tension softened like putty. I couldn’t remember what I’d come out here to do and what had driven me here. My hands dozed in my lap as I drifted and drifted on the incoming tide.

It seemed the most natural and sensible thing to slide down onto my back. I knew I’d be perfectly safe in my gently rocking cradle, as certain as an infant, as I watched two eagles in a love dance high above me.

Suddenly, the silver blade of a jet bisected the sky. I smiled at this odd intrusion, smiled as the eagles’ ballet continued in spite of it and wondered which was the greater miracle.

I breathed back into myself and patted my skin into place before rowing back across the silver bay. Our neighbour gave me a little wink and wave as I tied up the skiff and clambered back on board. He reminded me a little of my dad and I had the feeling he understood what I was doing drifting around the bay.

A few helping hands and sympathetic suggestions determined the engine alternator was the culprit this time, which meant another run down the channel to Hardy to get it fixed. With luck we would be fishing again in a couple of days. In the meantime I knew to lay low and keep myself occupied.

Un-Dressing Salmon

How do you dress a salmon? In fishnet stockings, of course.

Dressing a salmon is kind of a misnomer. Getting dressed usually means you add something to something—clothes to a person or sauce to a salad or stuffing to a turkey. But when it comes to salmon, you take things away: all their guts and gills.

The Fisher Queen

The Fisher Queen