- Home

- Sylvia Taylor

The Fisher Queen Page 8

The Fisher Queen Read online

Page 8

Tears welled up. I couldn’t trust myself to speak, and let the gaff drop to my side. The last thing I’d expected was this much conflict between us. I could stand anything but that, after the end of my marriage less than two years ago and the pitiless divorce and husband I was still not free of.

“Look, if I ever yell at you like that again, you can kick me in the ass. Okay?”

“What?” I burst out laughing through the lump in my throat. “Are you crazy? I can’t do that.”

“I’m serious. I deserve it for being such a jerk. Okay, how about this. We’ll be in Bull Harbour soon and I’ll buy some more flashers and Perlon on credit. It’s going to be a sunny afternoon, so how about we take your salmon sandwiches and go around the corner from the camp to an old Indian village site I heard of and look around for a while? Then I can just finish up this stuff tonight. Just put down that gaff, okay? I don’t want to end up in Davy Jones’s locker.” He chuckled and flashed his gigolo smile.

Just before the Nahwitti Bar, we noticed a distinctive orange hull anchored by itself in a small bay. Paul radioed on the short-range Mickey Mouse, hoping it was our friend Gerry from False Creek. He was just about to give up when Gerry’s unmistakable Kris Kringle voice broke in. He and his six-year-old son, Peter, and his deckhand, Mike, had just arrived at the top end and were anchored up getting ready to start fishing the next day. When he heard of our gear disaster, he graciously offered to lend us one of his spare cannonballs so we could fish with all six lines. He’d heard the fishing was slow everywhere and likely knew we were broke from scratching around for the last five weeks and couldn’t afford the cannonball, the most expensive part of trolling gear. We decided that after our little exploration trip and buying more regular gear (on account) in Bull Harbour, we would run back out to tie up with Gerry in the bay that night.

“Hey. How would you like to go straight to the old village site now and have lunch? Looks like it’s clearing up a bit and it’ll be nice there.” Paul glanced over at me refolding and stowing charts in the wheelhouse and pushed the throttle forward to pick up speed after the choppy bar.

“That would be great. I’d love that,” I said, stepping over to smile up at him. “What about the gear?”

“We can pick it up on our way back out to tie up with Gerry in the bay. We have to get it on credit, so I’d rather be there around dinnertime when there won’t be so many people in the store. Jesus, it’s embarrassing.” His face darkened. “What the hell. Let’s go explore. I’ve heard you can still find some beads. Pack up our lunch and get ready. It’s just a few minutes away around the bottom end of Hope Island here.”

We anchored in the idyllic little bay and rowed to a perfect white crescent beach rising to a grassy knoll bordered by salmonberry bushes, trembling aspens and towering pines. Remnants of a wooden two-storey house set back in the trees and stunted corner posts on the knoll were all that was left of the Native people’s village. But the graffiti of carved names and painted We been here and carpet of smashed booze bottles revealed later visitors.

We stood in front of the tumbledown front door. “Imagine seeing this out your front door,” I said, looking out over the glittering bay and islands dotting the channel. “It’s paradise. Everything you could want is here. Look at the next little cove. I can see the gorgeous colours in the tide pools from here. And look at the size of the mussel shells. I’ve never seen them so huge. Let’s go down there.”

“And all some people want to do is come here and wreck it. Look at all this garbage. What a bloody shame. Maybe we can find some beads for you. I know you love that kind of stuff.” Paul scuffed at the mossy soil and glass shards.

“No, it’s okay. I don’t feel right about it. Let’s just leave things alone.” I felt a heaviness in my chest and took a deep breath to lift the sudden pall. The rising tide had already covered much of the beach, so we clambered along the rocky shoreline, carefully avoiding the brilliant kaleidoscope of sea life.

“Paul, look at those anemones. They look like emerald-green broccoli standing up in a grocery bin and as soon as they sense us coming they pop into themselves. Now they look like St. Patrick’s Day doughnuts with chocolate centres.”

“Wow, they do. They’re making me hungry. How about one of those sandwiches out of your kangaroo pouch?” He gave the bulging front of my yellow anorak a playful poke.

“Once we eat our sandwiches, let’s gather some of those giant mussels on the rocks for dinner tonight with the boys. They’ve got to be six inches long. I’ll use this aluminum foil and sandwich bags to put them in, and carry them in my front pocket back to the boat.”

“Okay, pioneer girl, let’s go hunt down dinner.” Paul smiled and brushed the mop of sun-streaked hair from my eyes.

After we filled my pocket with mussels, I allowed myself one treasure to mark this astounding day—an exquisite abalone shell with vivid pearlescence that I’d found near the knoll. I whispered my gratitude as I held it to my chest.

When we returned to Bull Harbour camp, I asked Anne, the first aider/accountant, if she knew anything about the old village site. Her grey eyes went stormy.

“That site has been horribly ravaged by non-Natives doing so-called digs, including using bulldozers,” she said, her mouth going hard as she turned my shell over and over in her hands. “They sell everything they can find, including little beads—disgusting. They’re no better than the European traders that came here 200 years ago. They’re still ripping off the Natives and can’t even leave that old site in peace.”

As I turned to join Paul hurrying to the boat, I suddenly mentioned we had gathered mussels from the rocks for our dinner.

“Honey, I wouldn’t eat those if I were you. Dump them overboard.” Anne pointed to a bulletin tacked to the corkboard in the office. “There is a possible red tide and they might be contaminated. Fisheries was here taking samples two days ago and gave us this notice to post. Didn’t you hear it on the Coast Guard radio? They will issue a report in a couple of weeks. In the meantime, don’t eat any shellfish from the north end. It could be deadly. The red tide is like clouds of toxic bacteria that just comes out of nowhere and contaminates shellfish. It’s deadly to humans and takes weeks for the shellfish to flush out in the sea water. Promise me you’ll throw that stuff overboard.”

I solemnly promised and hugged her goodbye in gratitude. Paul watched dumbfounded as I poured the bucketful of mussels and sea water overboard and told him why.

“Jesus, we really dodged a bullet on that one,” Paul said. “Good thing you told her. They don’t know for sure yet, so maybe they were okay. Oh well. C’mon, let’s get untied and get out to meet Gerry while it’s still light enough for repairs.”

After rounds of handshakes and hugs, Gerry and Mike helped Paul restring the steel wire and make up more gear lines while I cooked us up a feast—spaghetti and halibut steaks.

We were poor as peasants but ate like royalty on the gifts the sea provided: salmon, red snapper, halibut, ling cod and the occasional crab or smoked salmon shared by our Bull Harbour neighbours. All that high-end protein and omega-3s along with the porridge and potatoes and brown rice created a high-octane fuel that powered us through 16-hour days and honed our bodies to bone and muscle. I was connecting deeply with my body again, trusting in its strength and agility. No matter what happened over the next three months, that recovery was worth everything. I was becoming me again.

And later that night, as I stepped out on our deck to bring in the bag of fresh fruit Gerry had surprised us with, I turned a slow circle, arms outstretched to the tangy air and fiery sunset, the silent dark forest, the two old wood boats bobbing together companionably, the light from our cabin full of savoury smells and cigarette smoke and laughter, and filled myself up with it.

Salmon Prince

There was nothing I wouldn’t do. I would turn myself inside out to prove I could do it. Anything. I was fierce: a lioness padding around my 39-foot territory. Bring it on, I snarled. T

hink I’m too girly? Bring it on. Think I’m too little? Bring it on. Think I’m too citified? Bring it on. I could sleep less, eat less, learn faster, make fewer mistakes and be more cheerful than any deckhand in this fleet. And when Paul told me not to, because it was too heavy or too dangerous, I’d wait ’til he was napping or distracted and then I’d do it anyway, and find a better way to do it.

It was a rare and glorious day of oily smooth seas, caressing breeze, benign sun and all the world rejoiced—at least, this part of it did. Those were the days so full of God’s grace, when Gaia was her most loving and tender and I couldn’t imagine being anywhere or doing anything else.

There’d been nothing on the lines for the last two pulls and there wasn’t another boat for miles. We’d scrubbed and organized, repaired and patched, tied more gear and checked the glistening beauties lined up in their chilly beds like dollars in the till, their gutted bellies chubby with crushed ice in the hold.

I was secretly thrilled when Paul announced he was hitting the bunk for a nap. The autopilot was working for once and all I had to do was keep an eye on things. “Don’t get yourself into trouble,” he said, reminding me he wouldn’t hear me through sleep and the engine’s thrumming.

We were trolling our way back to Bull Harbour and that would take hours. I was so excited it was hard to act nonchalant. I felt like a kid left at home alone and I was going to do everything. Alone. I was going to catch a Salmon Prince.

I’d surprise him. When he woke up, I’d wait ’til he staggered out on the deck, blinking and yawning, glancing around for evidence of my folly. He’d see none. I’d pretend to be bored and make small talk. Then I’d casually mention that something got left behind the last time we dressed and iced the fish. He’d sigh and bitch about dried-up fish and lost money and yank the bin cover off. And there my prize would be. Huge. Perfect. Magnificent. And worth three days of groceries. Paul would never interfere with the fish on my side again and I’d pull in my own damn smileys. And I would smile and smile, just like the name intended me to do.

I took a deep breath and climbed into my Hellys and gumboots and cinched them good and tight. I did an all-points check, walked carefully along the deck and eased myself into the cockpit. No vaulting—hard to pull in a smiley if you’re lying in the cockpit with a broken leg. One more scan and a prayer to the Salmon Spirits. I checked the gear, his side first. I willed everything into silence. If he woke up it would ruin everything.

The usual pull-pull, grab-throw of the gear, elevated to a martial art: be the motor lever, be the spinning gurdy, the steel line, the clips, hoochies and hooks, the flashers, swivels and leads. But there was only a little drowned sockeye, which I set aside for the oven, and a couple of brown bombers, the pesky local rock cod, which I graciously unhooked and released. Undaunted, I knew my prize, my Salmon Prince, awaited me on my side of the boat—the good side.

I paused to scan around us again. No point making a big score if someone ran into the boat 20 miles offshore. The time was nigh and I moved to the magic side.

Bow cable: nothing. Main cable: nothing. How could 30 gear lines be empty? Pig cable: I counted down 10 lines, only 5 more to go. If they were empty, I would lose my chance. Paul would be awake before the next pull. Please, please, please be there.

And on the 14th line, the Salmon Prince.

I felt him before I saw him, a slight thrumming tension as I unclipped the Perlon from the line. Re-clipping it, I nudged the motor lever forward to stop the cable from spooling onto the gurdy drum. My heart kicked up a notch as I whispered instructions and encouragements to myself: “If you don’t secure the line he could yank it out of your hands. Don’t jerk the line or make sudden noises, or he’ll bolt. If he’s not hooked hard, he’ll jerk his head and pull the hook out.”

With both hands I transferred the clip to the holding wire on the inside edge of the stern. I breathed deep and eased into stillness, utterly focused. The world telescoped down to a scarred wooden ledge, a Perlon line and five feet of silky water.

I seduced the line in, hand over hand, a few inches at a time. The surface of the water bulged slightly and there was his dark back fin and, miles behind, the tip of his tail, languidly sweeping from side to side. I drew him to the stern, transfixed by his muscular, graceful beauty. He showed me first one side, then the other. Am I not exquisite? he said. Am I not a miracle of perfection?

I understood why the ancients sang songs of love and gratitude to the plant and animal beings around them. I understood why they asked permission to take lives that sustained their own, why they performed rituals of gratitude and humility. It wasn’t just to ensure future plenty but to honour their partners in the dance of life and death.

I felt my heart swell with joy and the cooling tracks of tears on my face. Shaking, I reached for the spiked gaff. He was too massive to pull in by the line. The hook had pierced just inside the corner of his mouth. Even if the hook held, the line would slice my hands open hauling him in. My only chance was to hit him precisely behind his head with the club side of the gaff to stun him so I could haul him over the stern by the hook side.

I brought the gaff down and missed. He swam gently. I hit again and missed. By then I was weeping. He continued swimming gently. “Please help me, I don’t know how to get you in,” I whispered. My civilized mind recognized the madness in this, but it came from a great distance. I couldn’t bear to club him again, to submit him to my clumsy attempts.

This time I reached down as far as the waist-high stern would allow. Balanced on the transom, I tipped forward and slipped the gaff hook under his gill. What madness was this? One lurch and I would launch headfirst into the chuck to be his briny bride forever. But he held steady and leaned gently to his other side. I wondered if I was just dreaming.

“I’m going to pull you into the boat now,” I crooned. Easing back to the floor, I started to haul him out of the water. He was impossibly heavy and I was too short to get the leverage I needed. I grunted and strained and begged him not to thrash, begged every deity I knew and some I didn’t to help me. I was shaking with tension and wondered how long he would tolerate dangling in another element. Paul had lost a monster spring the day before. Just as he was pulling it over the ledge by the gaff the fish freed itself with a mighty twist and flung itself back into the water. In my other life I would have cheered it on, but we were so damned broke I cursed its freedom. It felt like someone had opened my wallet and torn up the money in front of my face, or stolen my food and shoes.

The Prince’s head appeared at the stern ledge and I crouched lower, straining every muscle in my body. The ocean and I had given birth to this beautiful slimy creature and with one more grunting cry he slithered over the stern and into the cockpit, where he slowly flapped and gasped. I couldn’t bear to see him drowning and struggled to lift him into the bin, cradled in my arms. I stroked his luminous flank once, thanked him for the gift of himself and then hit him hard, precisely behind his head.

When Paul stumbled out onto the deck, blinking and yawning, he glanced around for signs of my folly. Instead, he found me sitting quietly on the hatch cover, gazing at the hazy line of land.

I was too tired to lift my prize into the dressing tray—he did. He didn’t insist on dressing him—I did.

He took a photo of me in my Helly Hansens and gumboots. I braced the Prince against me, hands in gills, knees bent from the weight. His nose was at my heart, his tail at my knees. He was as wide as my body was thick.

Bob, the camp manager, weighed him in at 52 pounds and called everybody down: his wife, Marji, Anne the first aider/accountant, his son-in-law, Mike, and the two summer boys who were shovelling ice and packing fish on the wharf—all the folks who were becoming like family. My Prince was the best they’d seen so far that year. The admiring nods and incredulous stares of the camp staff and other fishermen who wandered over to find out what the fuss was all about made everything worthwhile: the worrying, the weariness, the bangs and cuts, the raw wound

s.

My hands took the worst of it. Every morning an agony. I had to flex to get them moving, and the sores that had dried up overnight, thanks to my spectacular immune system, cracked open and bled. Problem was, we just couldn’t find industrial-strength rubber gloves to fit. When the gloves slid back and forth, especially when I dressed fish, I struggled just to keep the damn things on. I even tried wearing an old pair of wool gloves inside the rubber gloves, but that was like trying to do surgery in oven mitts. Then I tried duct-taping the gloves on, but that just took the skin off my forearms. Since I constantly handled rough or pointy objects and razor-sharp knives on the pitching deck of a boat—much like preparing Christmas dinner while your house is spinning in a tornado—my hands were a roadmap of injuries. So I went gloveless and prayed I wouldn’t get blood poisoning.

Apparently, fish slime is particularly toxic to humans when introduced by knife cut and can send susceptible people off to the closest hospital, hopefully faster than the blue line of poisoning creeping up their arms. I never did get blood poisoning, but I did get the dreaded Fish Bite. It doesn’t kill you, but it hurts so much you wish it would. It comes from fish slime rubbing on your hands, particularly with loose gloves, and eats away your skin like battery acid. Next thing you know, you’ve got raw weeping patches between your fingers that are damn near impossible to heal in dirty, wet conditions. The longer you ignore them, the worse they get, until your hands feel like they’ve been caught in a leghold trap and you just want to chew them off.

While Paul was unloading the couple of handfuls of fish, I stripped off my rain gear and went down to the fo’c’sle to change for the usual laundry-and-shower extravaganza. Even without a mirror, I was shocked to see the state of my thinning body, besides my emerging ribs and hip bones. The light from the little skylight in the fo’c’sle roof revealed so many bruises I looked like the Tattooed Lady at the county fair. My body was an illustrated account of every collision with something much harder than myself over the last five weeks, which was pretty much everything. It was not the climate or place for cushioned objects. They’d just get mouldy and wouldn’t take well to being scrubbed down with industrial cleaners.

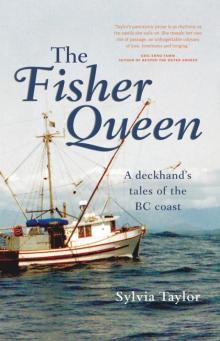

The Fisher Queen

The Fisher Queen