- Home

- Sylvia Taylor

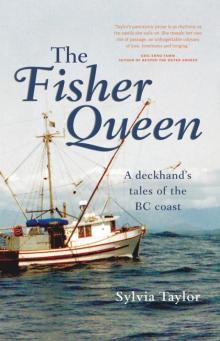

The Fisher Queen Page 9

The Fisher Queen Read online

Page 9

Everything was bare and spare and hard. Couple that with almost constant lurching, bouncing and bangs, and enormous amounts of water and slime, and you had a perfect studio for hematoma art with you as the canvas. Each technicolour lump was brushed with colours from hell’s sunsets: obsidian, aubergine, vermilion, puce. They were war wounds and medals to display and tell stories about on harbour days. One thing for certain, fishing was not a good vocation for a hemophiliac or people with bird bones. Luckily, I had bones with the density of lead, or I would have been in a lot more pieces than I was before.

I was never more thankful for my hardy European peasant bones than the day I did a flying camel into the stern cockpit feeling particularly jaunty one morning. For once it didn’t look like the seventh ring of hell outside—amazing how cheerful I felt when I didn’t start the day in mortal terror. Eschewing my usual careful, crab-like clamber, I jumped up and went horizontal. Unfortunately, I stayed horizontal, fell five feet into the cockpit and landed on the huge knobby metal propeller housing.

Before the pain hit, I was aware I couldn’t breathe, which helped me stay very still. The entire universe narrowed down to one tiny point—me, crumpled and terrified. I wondered how dearly I would pay for my gymnastics. Out here, help was hours away, not minutes.

I had knocked the wind out of myself and was now left to determine whether or not I had shattered everything from armpit to ankle. By that time Paul had come out on deck and, not seeing me, began frantically bellowing my name. I wasn’t overboard, but this could be worse. I summoned up a weak mew and raised my free arm. I was lying on my left hip and didn’t want to move anything else.

“What the hell did you do now?” he hissed and eased down next to me. His taut, suddenly grey face scared me even more.

No matter what, I had to get out of the cockpit, so we started moving one small part at a time until I was standing again, shaky but okay. Miraculously, my hip bone had missed the housing by a couple of inches, but my rump—what little there was left of it—had not. Several layers of clothes, including the usual four sweaters, had cushioned the rest of me.

That escapade left a monumental bruise worthy of any harbour day. Slightly horrified by my body inspection, I changed and grabbed the laundry bags. When Bob stopped me for one more congratulations on the smiley, he noticed my poor little paws, winced in sympathy and told me to go see Anne in the office, who would fix me up in no time. She did, God bless her.

Someone was taking care of me. A motherly woman who wasn’t just doing her job but had opened her heart to protect and nurture me. Her gentle kindness drew more tears from me than the terrible pain of my hands being soaked in antiseptic solution. As I wept out the fear and pain and loneliness and burbled my apologies, she paused from massaging my hands with antiseptic cream, held me in her arms and rocked me, murmuring over and over, “It’s okay, honey. I know, I know. It’s so hard. You’re such a brave girl.” In that hour, I loved her more than anyone on earth and swore I would never forget her.

After she had salved and bandaged each finger she marched her substantial self over to our boat and reamed Paul out for “letting that poor wee girl’s hands get so bad” and she “had a good mind to keep her here ’til her hands healed up.” She only released me when he promised not to have my hands anywhere near water or slime for at least a week. Because if my hands weren’t healed the next time she saw me, she would send me home on the next packer and he would not be welcome in that camp again.

Paul sheepishly agreed and she marched back up to the office to special-order a box of the smallest, heaviest-grade rubber gloves she could find, no charge, to be brought in by float plane the next day with the mail.

Ten days later, Anne stood on the dock, stern-faced, as I held out my healed hands for her inspection.

“That’s good honey, that’s real good,” she said, giving Paul a brief acknowledging nod over my head.

Indian Candy

During the first weeks in Bull Harbour I became enchanted with the notion that I could take a dead animal, hang it in the wind and then eat it. Of course, there was a lot more to it than that, but that was basically it: kill it, dry it, eat it. People all over the world had managed for millennia without refrigeration, for the most part, by preserving food through dehydration. Amazing. Why would just removing moisture keep meat from rotting and killing me?

I was amazed that more fishermen didn’t do it with salmon. It wasn’t like it would eat into their profits. There was always a belly-cut fish not worth selling or a dead undersized or an illegal fish on a hook. Why throw it overboard? We were out there spending fuel and time anyway; we might as well take advantage of the free groceries. It might have had something to do with the redneck attitude that only poor (read lousy) fishermen eat fish. And it wasn’t just that they got turned off fish because they had to handle them and were sick of the sight of them. They believed that the only reason you’d eat fish is because you couldn’t afford to eat anything else.

So the High Rollers stuffed their boats to the gunwales with steaks and roasts and hams and mountains of junk food. They were the only ones who could afford it and they knew it. It was an ancient form of conspicuous wealth, like potlatches and fat wives. Of course, the irony here was that their wealth was killing them with cholesterol.

The rest of us may have been poor, but we were certainly healthier. We hadn’t even caught a cold, for God’s sake. Our squeaky-clean diet and intense physical activity must have compensated for indulging in too much beer, coffee and cigarettes. Then there were the jujubes, those cheerful little darlings that called to us from the camp shelves and we could never resist. Funny how such an unassuming thing we took for granted at home became elevated to a guilty pleasure just because it was uncommon out here.

The marine menu pooh-poohed by the High Rollers was coveted by land dwellers, who spent their conspicuous wealth buying the same stuff tarted up in trendy restaurants. But no matter how much they paid, it would never come close to what it tasted like fresh from the chuck. In less than five minutes I could have a little salmon dressed, deboned and in the oven. The oil stove was always going anyway, so why not cook fish while you worked and rolled your guts out?

But where salmon really shone was when it was air-dried. Known as Indian Candy because of its ruby colour and sweetish taste, it was one of nature’s best fast foods. That’s not to say it was quick and easy to make, just to eat. And not that it was always delicious, just when you made it right. And boy did I make it right.

The First Nations people knew what they were doing when they filleted and cut their fish into long strips to dry in the wind. They knew that direct sun would toughen and seal the outside before the inside had a chance to dry. They knew that wide slabs and chunks wouldn’t dry inside either. So do you think the Round-Eyes paid any attention to that? Nope, most of them would just string up a whole flattened-out, deboned salmon from the boom and wonder why it went mouldy. Learn and adapt, gentlemen, learn and adapt.

Occasionally I would be told during harbour days that people thought we were an Indian boat because of the racks of salmon hanging from our boom. I was flattered instead of angry. Then they would tell me we couldn’t be Indian because our boat was too clean. Then I was angry instead of flattered. The same people who made snide remarks about the predictable dirtiness and drunkenness of Natives seemed to be the ones nursing the worst hangovers on the nastiest-looking boats. Historical resentments and prejudices still simmered on both sides of the racial divide.

In Paul’s case, people never could quite figure out his racial pedigree and it took weeks before I was told the reason for the occasional sideways look when we were together. Racial mixing aside, his genetic cocktail of Scottish, English, German, Mohican, African-American and God knew what else had created a specimen that most men wanted to be and most women wanted to have.

I became a culinary bloodhound and sniffed out anyone who had air-dried fish and pumped them for information. Through much tria

l and error, I devised the perfect technique. I could have won the gastronomic equivalent of a Pulitzer for air-drying salmon. It was so good people told me that I should sell it. I probably could have made more money with it than fishing, that’s for sure, but it was so labour intensive I made it only for our use and the occasional free sample, and once as a gift.

Being of the Nordic persuasion, my father was crazy about fish, any kind in any form, but especially pickled and preserved. I got the brilliant idea to surprise him with a Father’s Day gift fit for royalty, a box of my very best Indian Candy. I imagined his eyes sparkling with delight at the colour and smell, rhapsodizing over the texture and taste in that contained northern way, murmuring, “What a kid.” I also imagined my mother, her Tuscan sensibilities informing him that he would be enjoying my gift in his workshop, as quickly as possible, a value-added scene for my amusement.

Ever the info hound, I discovered the best way to send the salmon was either vacuum-sealed (no chance of doing that up here) or wrapped in many layers of paper towel, then newspaper. Plastic wrap would encourage mould. Besides, it would only be a few days, a week tops, until it arrived in the small BC Interior town of Clinton. It wouldn’t smell yet and no one would be the wiser.

Excited as a kid at Christmas, my new pal Anne snuck the salmon on the mail delivery float plane the next day. Loaded with postage, it began its journey from the watery west coast to the arid Interior. Anne and the camp crew were so caught up in the fun of this Father’s Day frolic they let me call my dad on their marine telephone to tell him to keep his eyes peeled for the surprise of a lifetime. I had included an eight-page letter and told him he could read about all my adventures while enjoying his gift. He loved the suspense as much as I did. Mum was crying so hard again, I had to share the secret with her on the phone to distract her.

But more suspense than we had bargained for was yet to come, as the salmon went on a little adventure of its own. Everything went swimmingly, until the day it arrived at their small-town post office. Dad had told his pal the postmaster that a very important parcel was on its way and to please let him know the second it arrived. The postmaster was just about to do so when he received a call from his area union rep saying they had begun a wildcat strike as of midnight and all mail currently in his possession was to remain undelivered until the situation was resolved.

Dutifully, the postmaster called Dad to tell him the package had arrived but unfortunately could not be released. My father, who had never done an illegal thing in his life, offered to sneak across the street in the middle of the night and have it slipped through the side window to him. No amount of pleading and cajoling could sway the postmaster: he was a devoted union man and besides, he would be fired if found out.

He told Dad not to worry, the strike would last only a few days. It lasted six weeks. Forty-two days of record-breaking heat, locked windows and doors, no air-conditioning and a smell that increased exponentially. The postmaster had to be there for every single one of those days to guard the mail. Even my gracious father was driven to retort, “Well, I guess you wish now you’d given it to me when it got here. Serves you right.” Three feet of Arborite and a labour dispute as turbulent as November gales separated the Druid King from his gift.

On the 43rd day, the postmaster unlocked and opened every window and door, marched across the street and handed my father the salmon-oil-soaked box.

“I could have her charged for sending something like this in the mail.”

“You’ll have to catch her first,” my father said and smiled benignly.

When Dad finally opened it on his back deck, dogs howled, babies cried and birds fell from the sky.

“It wasn’t bad at all,” he said the next time I called. “I just peeled off a few mouldy ones and the rest were great. Eating them in my workshop seems to work out best. I read your letter and eat the salmon and think of you out there doing all that stuff. It’s the best Father’s Day present I ever had. You’re really something. What a kid.”

Even hundreds of miles and a radio telephone between us couldn’t conceal my tears. I was living this life for the both of us and he was proud as hell.

Recipe for Sylvia’s Superlative Salmon Candy

Catch one small (four- to six-pound) salmon. Humpies are too oily, springs too dry, coho too costly, but sockeye are just right. In a pinch, use what the gods give you.

Before proceeding, remember to tell the fish how beautiful he is and thank him for the gift of his flesh for your well-being and enjoyment. Kill him quickly and compassionately and handle him gently at all times thereafter.

Dress the fish out squeaky, and I mean squeaky, clean. Remove all scales and slime. Do not leave one molecule of blood behind. Transfer to a bleached-clean PLASTIC cutting board. Cut off his head and tail, slit open to both ends and debone, being ultra-careful not to cut through the skin. You should have a flat, rectangular slab of salmon meat backed by skin.

Cover meat with several sheets of paper towel to absorb excess moisture and let rest for an hour in a dry, breezy area away from fumes and diesel exhaust and cinders.

Place another bleached-clean PLASTIC cutting board on top, flip over gently and remove first board to expose the skin. Make sure flesh is flat. Blot skin with paper towel to remove excess moisture, then expose skin side in a dry, breezy, preferably sunny (but not hot) spot for two to three hours to dry and toughen the skin. This is so when you puncture the skin to hang the slab up to dry, the holes won’t tear through the skin from its own weight. Bleach-clean the first board.

When the skin is dried and tough, puncture four small holes across the top end of the slab about an inch down from the upper edge. Place the first cutting board back on the skin, flip again and remove the second board and paper towel from the flesh. Bleach-clean the board and put away. Discard paper towel. The flesh should be deep orangey-red and glistening. Take a bleach-cleaned dressing knife and gently score the surface of the flesh in both directions with lines one inch apart to create a checkerboard effect. Then go back and carefully cut the lines deeper, about halfway to the skin. This will allow for air to penetrate the flesh without tearing the skin.

Weave a bleach-cleaned narrow dowel or long bamboo chopstick through the four holes at the top edge. Let rest for one hour to toughen the holes. Try lifting the slab partway up by the chopsticks to see if the holes will hold. If they start to tear, let the slab dry flat for another hour. Keep doing this until you can suspend the slab from the chopstick without the holes tearing.

While the slab is flat, sprinkle the following ingredients lightly and evenly over the cubes and gently rub in, making sure the spice mix gets into the cut-lines. This acts as a marinade for flavour and a curing substance to ensure safe preservation. Rub in this mixture once a day until the meat is completely dried and cured. Use a small amount, as it will accumulate over the days.

fine salt

garlic powder

onion powder

brown sugar

lemon juice (very sparingly)

Do not let the cubes get wet or dirty. Hang outside on the boom; works best in light winds. Hang inside when there is heavy wind, excessive heat or chance of wetness. Direct hot sun dries the outside too quickly and causes the inside to mould. This is a long process: give it approximately a week to ensure safe preservation.

As the skin dries and toughens, it will contract and pull the cubes apart. When this starts to happen, lay the slab down and carefully cut the lines just to the skin, but not through.

As the flesh dries it will shrink and become deep red and shiny. Anything else means mould. When ready, the flesh is chewy and the consistency of jerky, not mushy or tough. It should have only a very subtle fishy flavour.

Not only does cubing the flesh ensure safe and even drying and curing, it also creates convenient bite-sized pieces to pop in your mouth when you’re on the run or dirty. It’s also a fantastic high-protein lightweight food to carry on hikes. Just remember not to carry it wrapped

in plastic, especially when it’s warm, as this will create an orgy of bacteria.

The Quick Turnaround

When it comes to split-second timing and perfect choreography, Swan Lake has nothing on The Quick Turnaround. Heaven to some, hell to others, it is the surrealistic state in which an entire fishboat is dumped, cleaned and reloaded in one day—sometimes a few hours. A precision Swiss cuckoo clock at warp speed. It is the state that fishermen dream and pray about because it is usually only necessary when the fish are running hard and your hold is full.

So much about this business is timing. Along with the vagaries of weather, tides and government interventions, there’s the endless search for fish and the worry over having enough ice and supplies that you can afford and that will last as long as you need them to. It’s not like you can zip over to the corner store if you forget or run out of something, and the results of not having enough can be disastrous. Your boat may run on oil and diesel, but you run on coffee and cigarettes: the fisherfolk’s rocket fuel.

The second that crushed ice hits your hold, the 10-day clock starts ticking—that’s how much time you have before it melts or your fish flatten or go mushy. Watery ice? Less time. Forgot to put on ice blankets? Less time. Anchored up in a hot, sheltered bay to wait out the storm? Less time. The longer you stay out, the more layers of fish you lose.

Then there’s the running around like a lunatic from one area to another, frantically trying to find fish. The minute you hear of a good score somewhere, it’s too late. By the time you get there, closer boats have fished it out or the fish have moved on elsewhere. So you burn up time and fuel and your health for nothing and you limp back to the camp after 10 days to dump your slush and the few rats awash in it. But when all the stars align and all the plates spin on all the sticks just right, you fly into the Quick Turnaround.

The Fisher Queen

The Fisher Queen